Double up/down Strategy - Martingale Strategy

The Martingale strategy is one of the most talked-about approaches in forex trading. Known for its simple rules and bold risk management, it has both strong appeal and serious drawbacks. This article explains how the strategy works, its potential benefits and disadvantages, and where it may (or may not) fit into real trading.

The Martingale strategy is a trading approach that involves doubling the trade size after each loss, with the aim of recovering previous losses and securing a small profit once a winning trade occurs. Originally rooted in gambling theory, it has been adapted to forex and other markets, where it is seen as both an opportunity for steady gains and a source of significant risk.

There are a few reasons traders find Martingale attractive:

- Predictable outcomes – Under certain conditions, it can give results that feel almost guaranteed.

- No need to predict direction – You don’t have to be right about the exact market trend, which helps in the fast-moving forex market.

- Range trading fits well – Currencies often move within ranges and revisit the same price levels over time. Like grid trading, this suits the Martingale approach.

At its core, Martingale is a cost-averaging strategy. When a trade loses, you double your position size. This lowers your average entry price and gives you a chance to recover losses when the market turns.

But here’s the key point: Martingale doesn’t improve your odds of winning. Your long-term return still depends on how good you are at choosing trades and reading the market. The strategy simply delays losses. Also with the right conditions and enough capital, it can delay them long enough to look like a sure win.

Martingale Trading Explained

Martingale is a strategy that averages down losing trades. Each time a trade goes against you, you double the next position size. This lowers the overall entry price. The goal is that when the market finally turns in your favor, one winning trade is enough to cover past losses and still make a profit.

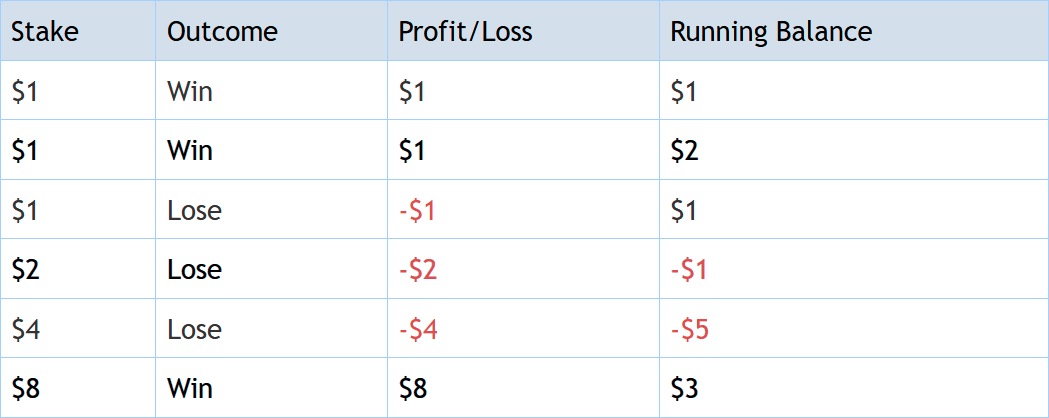

A Simple Example of Win or Lose

Here’s a basic example of how the martingale strategy works. Think of a trading game where you have a 50/50 chance of winning or losing.

This trade begins with a $1 stake. On a win, the stake remains at $1. On a loss, the trade size is doubled for the next round, a process often called “doubling down.”

With fair odds, a win will eventually occur. Because each loss was followed by a doubled stake, that single win not only recovers all previous losses but also adds the original $1 profit.

This works due to the mathematics of doubling: the final winning trade is always large enough to offset the total of all prior smaller losses.

A Simple Trading Approach

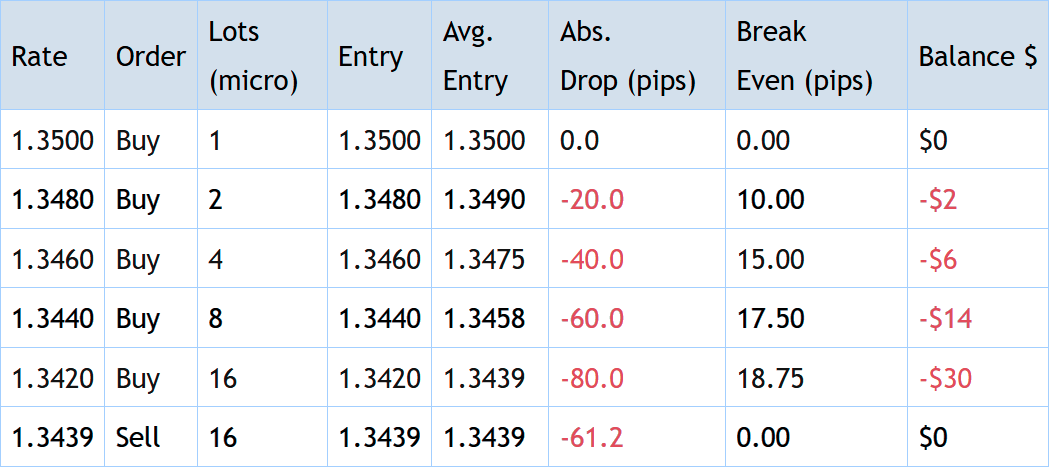

In real trading, outcomes are not limited to win or lose. A trade may close with varying amounts of profit or loss. The core idea of the strategy remains the same: a fixed price movement is defined as the take-profit and stop-loss levels.

Here’s an example. Take-profit and stop-loss is set at 20 pips.

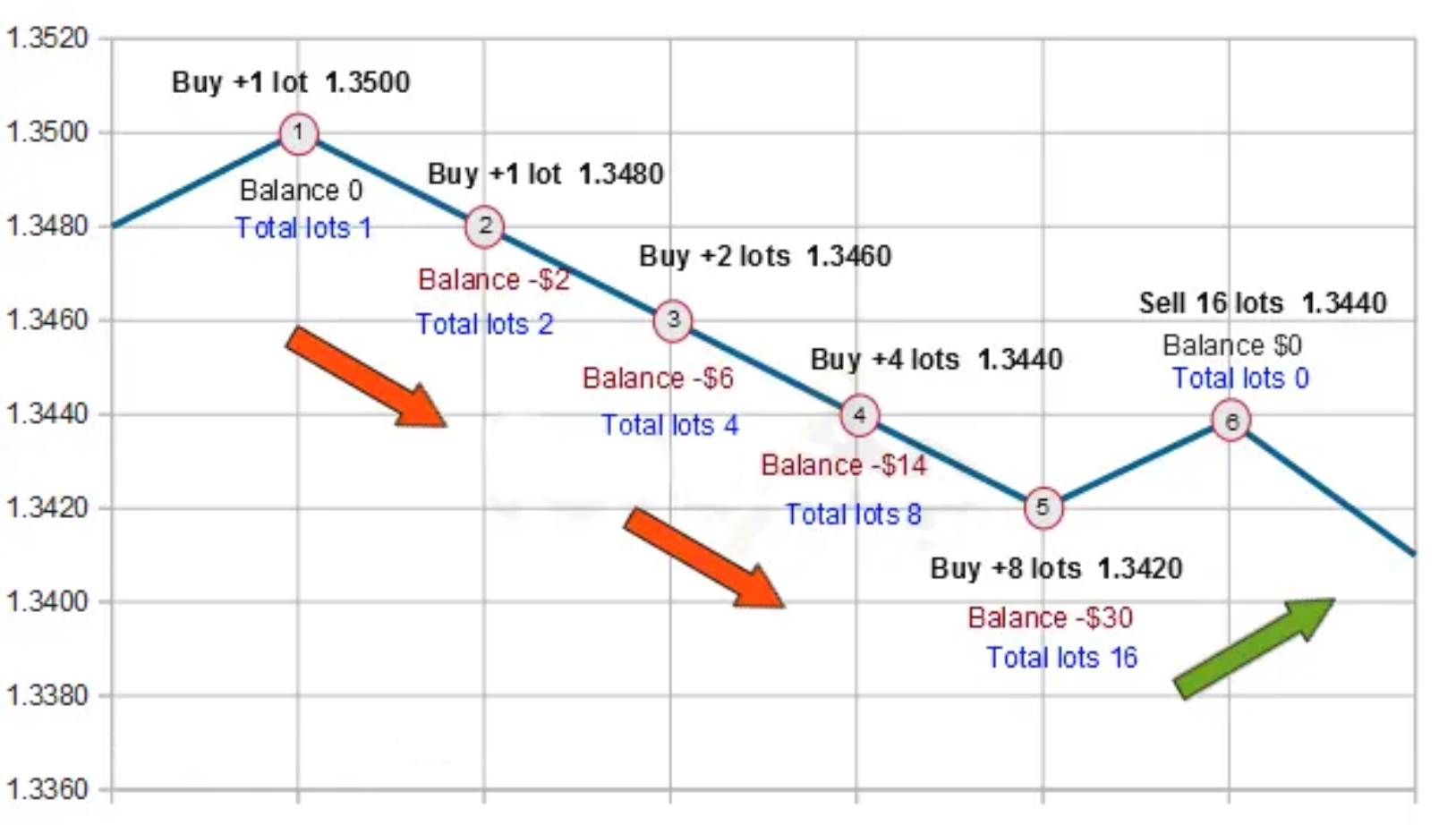

A buy order of 1 lot is placed at 1.3500. The price falls to 1.3480, resulting in a 20-pip loss at the stop-loss level. Instead of closing the trade, the position remains open and an additional order is added, doubling the size.

At 1.3480, another 1 lot is added, bringing the total to 2 lots. This creates an average entry price of 1.3490. The loss remains, but the price now only needs to rise 10 pips to reach break-even instead of 20 pips.

This method, called averaging down, doubles the trade size to reduce the price movement required to recover losses. The “break-even” column in Table 2 illustrates how each added trade moves the break-even point closer to the stop-loss level.

With the Martingale strategy, regardless of how far the market moves against the position, a recovery of one stop-loss distance is sufficient to return to break-even.

By the fifth trade, the average entry price reaches 1.3439. When the market rises to 1.3439, break-even is achieved. The first four trades close at a loss, but the profit from the final trade offsets these losses exactly.

Can the Martingale Strategy Succeed?

A theoretical Martingale system never loses a full sequence of trades because each losing trade is followed by doubling the next position.

In reality, such a system cannot exist. It would require unlimited capital and infinite time, which are impossible to achieve.

In practical trading, a limit must be set for total losses. If the losses reach that limit, the sequence is stopped, and the system restarts.

By imposing a drawdown limit, the strategy is no longer a true Martingale. It becomes a modified version that can fail under extreme market conditions.

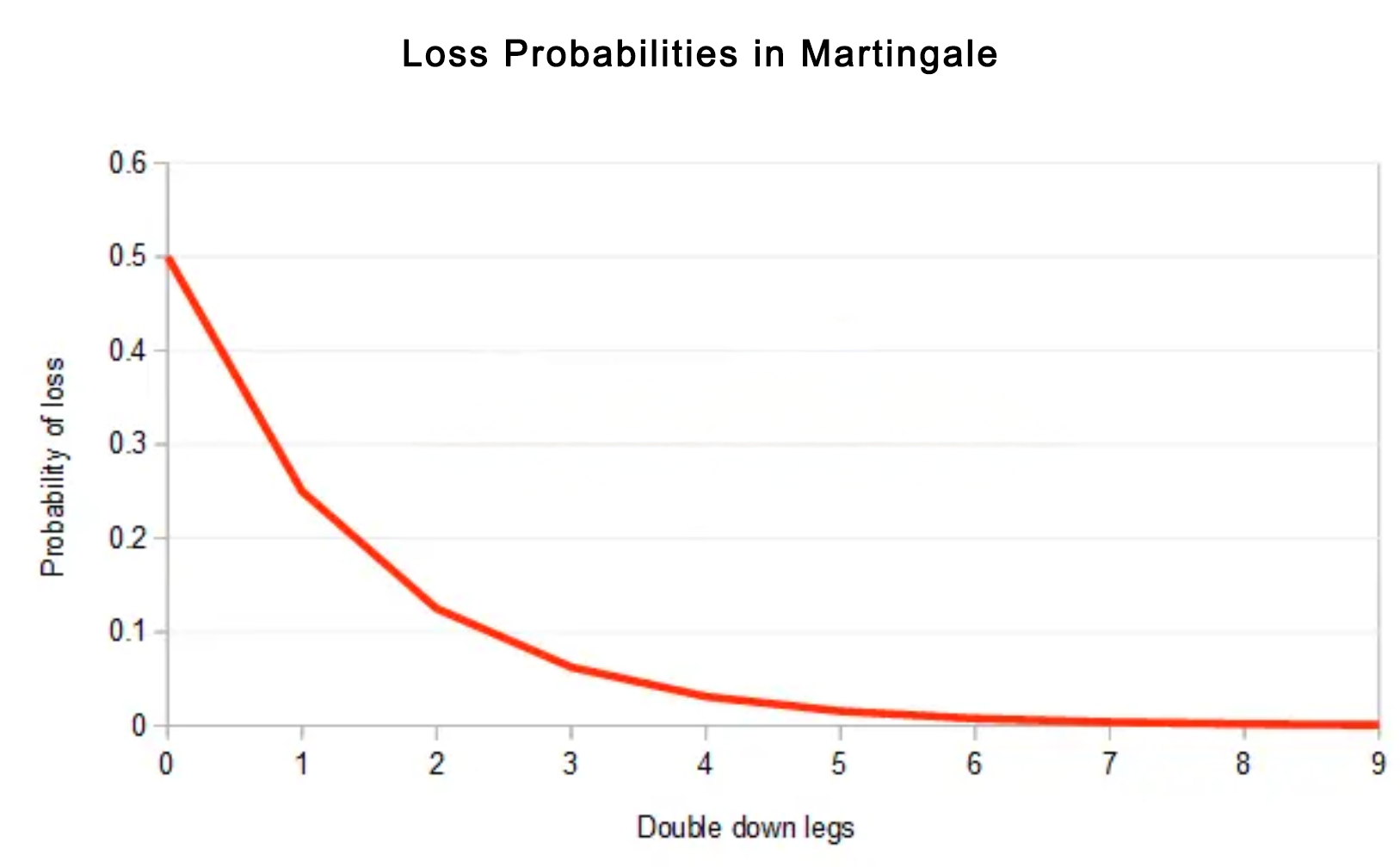

Doubling Down vs. Probability of Loss

The main trade-off in Martingale is this: the higher the drawdown limit, the smaller the chance of losing. But if a loss occurs, it will be huge. This is called the Taleb dilemma.

The more trades taken, the more likely a long losing streak will happen, which can wipeout all gains. In Martingale, trade size grows exponentially during losing streaks. For a sequence of N losing trades, exposure increases as 2N-1. If forced to exit early, these losses can be catastrophic.

Profits from winning trades grow only in a straight line, not exponentially. The total profit is roughly half the profit per trade multiplied by the number of trades.

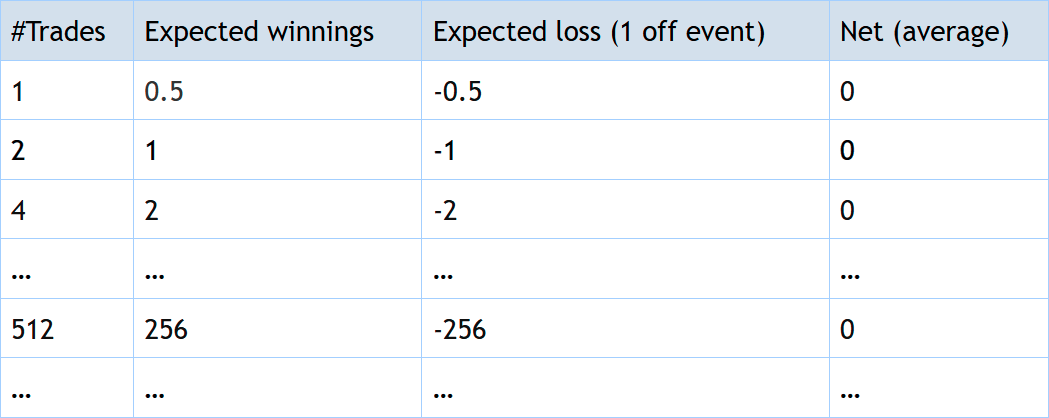

In this strategy, winning trades always produce a gain. If trades win 50% of the time(no better than random), the total expected profit from these winning trades would be:

E ≈ ½ N x B

where N is the number of trades and B is the profit per trade.

Even if trades win 50% of the time, occasional large losses can erase all gains. For example, with a 10-step doubling limit, the largest trade is 1024. A losing streak of 11 trades has a probability of (1/2)11, meaning it may occur once every 2048 trades.

After 2048 trades:

- Expected winnings: (1/2) × 211 × 1 = 1024

- Expected one-off loss: -1024

- Net profit: 0

This demonstrates that Martingale does not improve the odds of winning; it only delays losses. The risk-to-reward ratio is roughly 1:1. Unlike most strategies, losses are rare but very large, making risk management difficult.

Trend followers often prefer a reverse Martingale, which does the opposite: it doubles positions on winning trades and cuts losses quickly, following the trend instead of trying to recover losses.

Avoid Trending Currencies

The strategy works best in range-bound markets rather than trending ones. Trade sizes should be kept very small relative to capital using low leverage, so there is enough room to handle the larger positions that occur during drawdowns.

In practice, Martingale is most effective as a way to enhance yield.

Some traders suggest combining Martingale with positive carry trades, which means trading currency pairs with large interest rate differences, like long-only trades on AUD/JPY. The idea is to earn rollover interest from large trade volumes.

However, there are risks. Currencies with carry opportunities often trend strongly. Sudden corrections can happen, for example, if interest rates change unexpectedly or if risk appetite shifts and funds move out of high-yielding currencies quickly.

Analysis shows that Martingale performs poorly in trending markets over the long term. Many brokers also apply spreads to carry interest, and some don’t credit positive rollovers at all. Low yields mean trade sizes must be large to benefit, which is too risky with Martingale.

For trending markets, a reverse Martingale strategy is more appropriate.

Using Martingale to Enhance Yield

Martingale is not recommended as a main trading strategy because it requires a large drawdown limit relative to trade sizes. Using too much capital at once can lead to serious losses during a downtrend.

A safer way to use Martingale is as a yield enhancer with low leverage. The best opportunities are currency pairs that trade in tight ranges. Volatility tools can help identify suitable market conditions and avoid trending markets.

Martingale can handle trends only if there are enough pullbacks. It’s important to watch for breakouts of new trends, especially near key support or resistance levels. Strongly trending pairs, like Yen crosses or commodity currencies, carry higher risk.

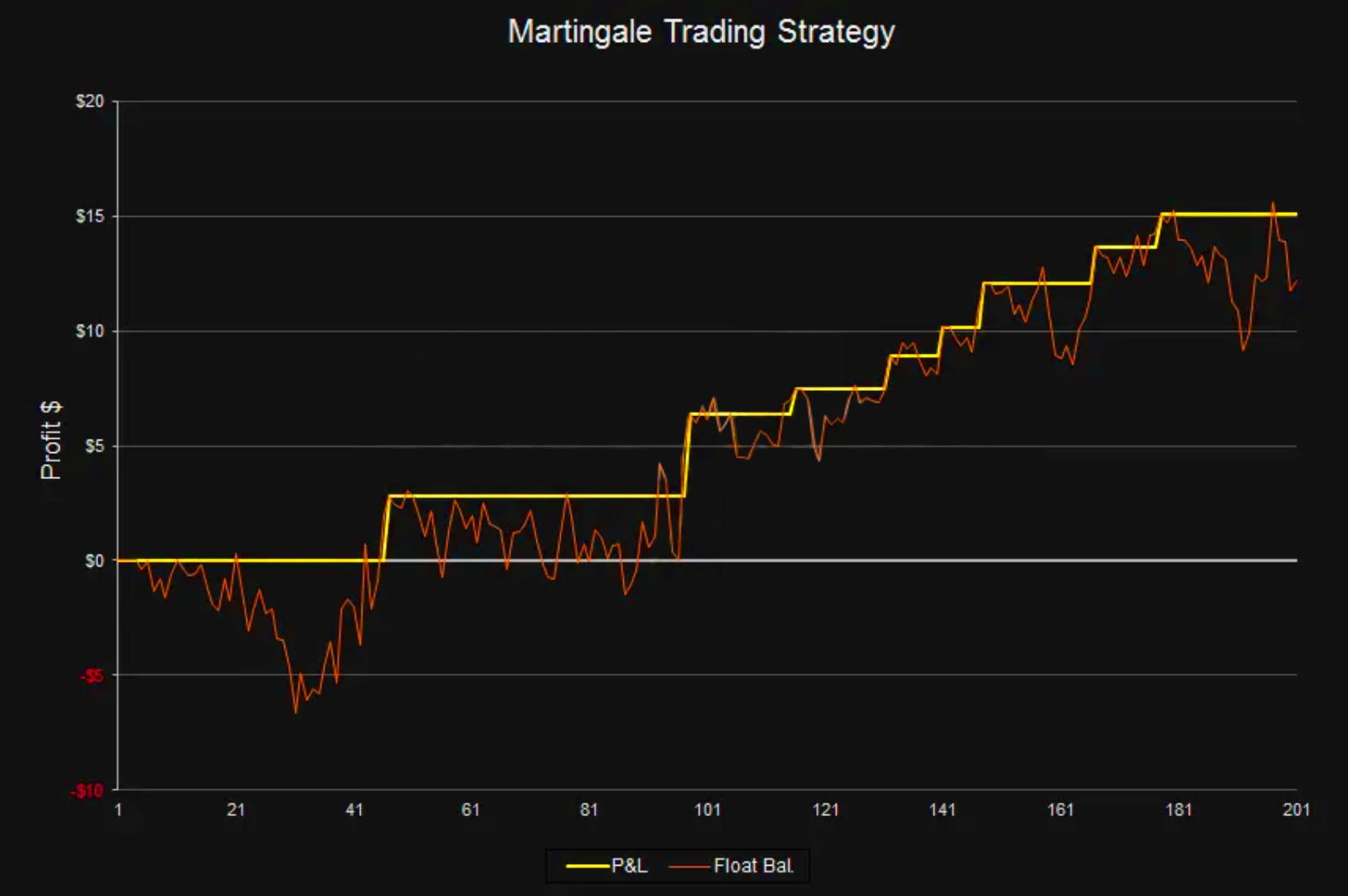

The image below shows a 3-month example of a Martingale yield enhancement strategy producing a 9% return. Low leverage helps keep drawdowns manageable.

Calculate Drawdown Limit

The first step is to decide the maximum number of open lots that can be risked. From this, other parameters of the strategy can be determined. Powers of 2 are used for simplicity.

The maximum lots determine how many stop levels can be reached before the entire position is closed. In other words, it sets the number of times the strategy can “double down.” For example, a maximum total holding of 256 lots allows doubling down 8 times, or 8 legs. The relationship is:

max lots =2Legs

If the position is closed at the nth stop level, the maximum loss is:

max loss = (2n-1) x s

Here, s represents the stop distance in pips used when doubling the position size. For instance, with 256 micro lots and a stop loss of 40 pips:

- Closing at the 8th stop level → max loss = 10,200 pips

- Closing at the 9th stop level → max loss = 20,440 pips

The average number of trades before a loss can be estimated using 2Legs+1. In this example, that equals 512 trades. After 512 trades, a string of 9 consecutive losing trades could occur, which would break the system.

Drawdown is best managed using a ratchet system. As profits are realized, lots and the drawdown limit are gradually increased. See the table below for an example.

This ratchet method can be applied in a trading spreadsheet. The drawdown limit should be set as a percentage of realized equity.

Warning: Martingale trading carries high risk. Capital at risk should not exceed 5% of total account equity.

Choosing an Entry Signal

The strategy requires a clear trigger to start buying or selling. Any dependable signal can be used, and the more accurate it is, the better the results and the smaller the drawdowns.

In this example, a simple moving average (MA) is used. A sell order is executed when the price rises above the MA by a certain amount, and a buy order is executed when the price falls below the MA. This approach focuses on trading minor reversals, also known as “fading” false breakouts.

A15-point moving average is used as the entry indicator here, but the MA length can be adjusted according to the timeframe and current market conditions.

This method is straightforward and easy to implement. More advanced techniques are possible, such as identifying divergences, using Bollinger Bands, applying different moving averages, or other technical tools.

Large breakout moves can quickly reach the system’s maximum loss limit. It is best to avoid trading near key support/resistance levels, during volatility squeezes, or right before major economic announcements.

Setting Take Profit and Stop Loss

Two key points need to be defined in the system:

- When to double-down – this acts as a virtual stop loss

- When to close trades – the take profit level

When to Double-Down

This is an important part of the system. The “virtual stop loss” assumes the trade has moved against the position. At this point, it is considered a loss, and the trade size is doubled.

If the stop is set too small, too many trades will be opened. If it’s too large, the strategy may become inefficient. The best stop distance depends on the market’s timeframe and volatility. Lower volatility allows smaller stops. Generally, a range of 20 to 70 pips works well in most situations.

When to Close

Trades in a Martingale system should only be closed when the total system is in profit. That means the net profit from all open trades is positive. Like grid trading, the trades must be treated as a group, not individually.

Smaller take profit levels, usually 10–50 pips, often work best. This is because:

- A smaller take profit is more likely to be reached quickly, allowing the system to close while profitable.

- Profit is compounded as trade sizes grow exponentially, so even a small target can be effective.

Using smaller take profit levels does not change the risk-reward ratio. While each gain is smaller, the closer win threshold improves the overall trade success rate.

Simulations

The table below presents the results from 10 simulations of the trading system. Each simulation can execute up to 200 trades. The starting balance was $1,000, with a drawdown limit set at 100% of that amount. The drawdown limit is automatically adjusted as the realized P&L changes.

The final balance reached $1,796, representing a total return of 79.6% on the initial capital.

The chart below illustrates a typical pattern of gradual profits. The orange line highlights the steeper drawdown periods.

Martingale does not improve the probability of winning trades. It mainly delays losses, which can last a long time if market conditions are favorable.

Pros and Cons of Martingale

Pros of Martingale:

- Follows clear trading rules that can be automated or programmed.

- Allows statistical calculation of profits and drawdowns.

- Can generate steady incremental gains if used correctly.

- Does not require predicting market direction.

Cons of Martingale:

- Focuses on limiting losses rather than increasing profits.

- Does not improve winning chances; only delays losses.

- Assumes markets behave randomly, which is not always true.

- Risk grows exponentially with losing trades, while profits grow linearly.

- Can lead to catastrophic losses due to limited capital.

- Risk vs. reward is balanced, but potential for one large loss makes it high-risk.

TradingLab is not an investment advisory or a similar financial advisory firm. We provide content based on economic, financial analysis, technical analysis, trading strategies, and other subjects found in economic, financial, and business literature.